The curse of modern brain science is that its founding father, Santiago RamĂłn y Cajal, was an incurable artist.

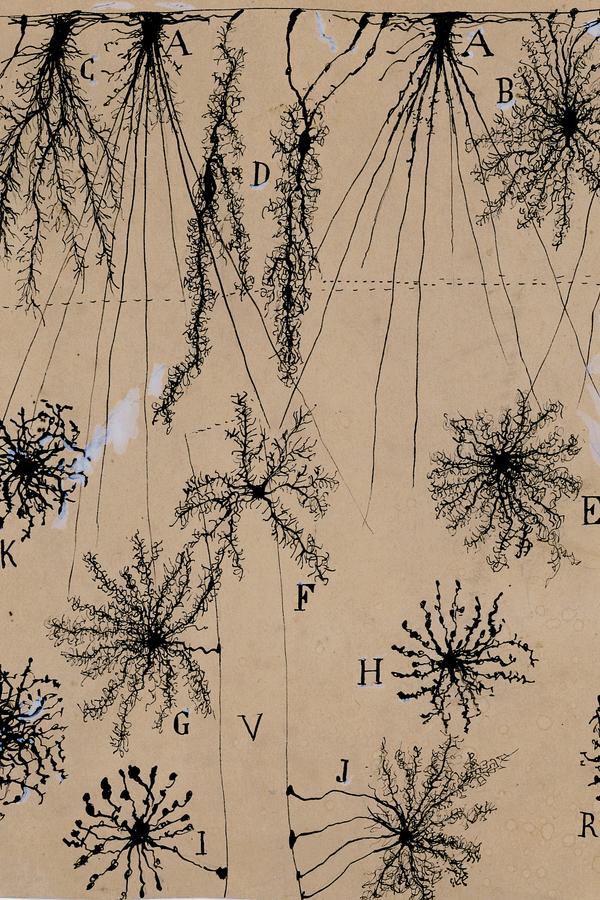

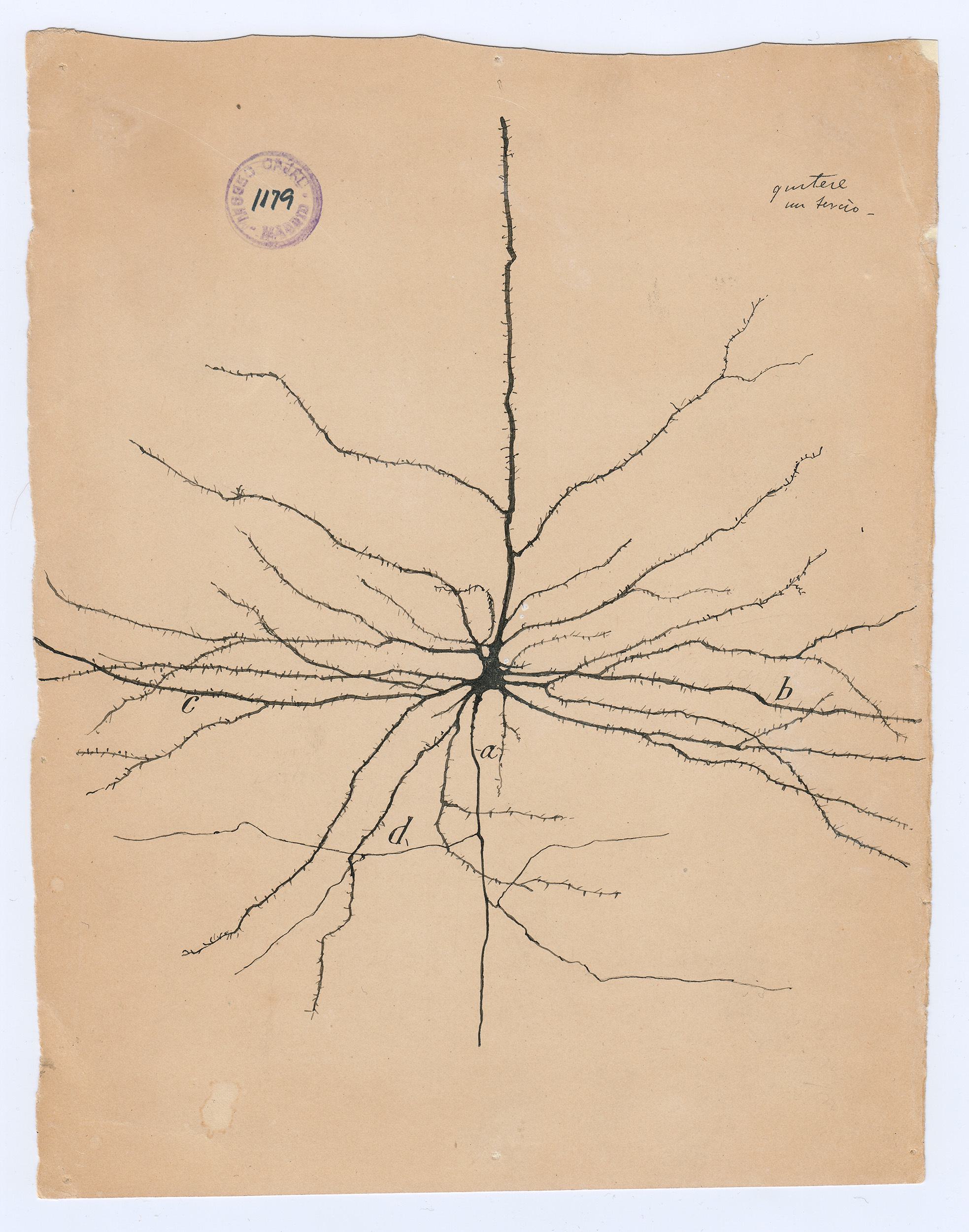

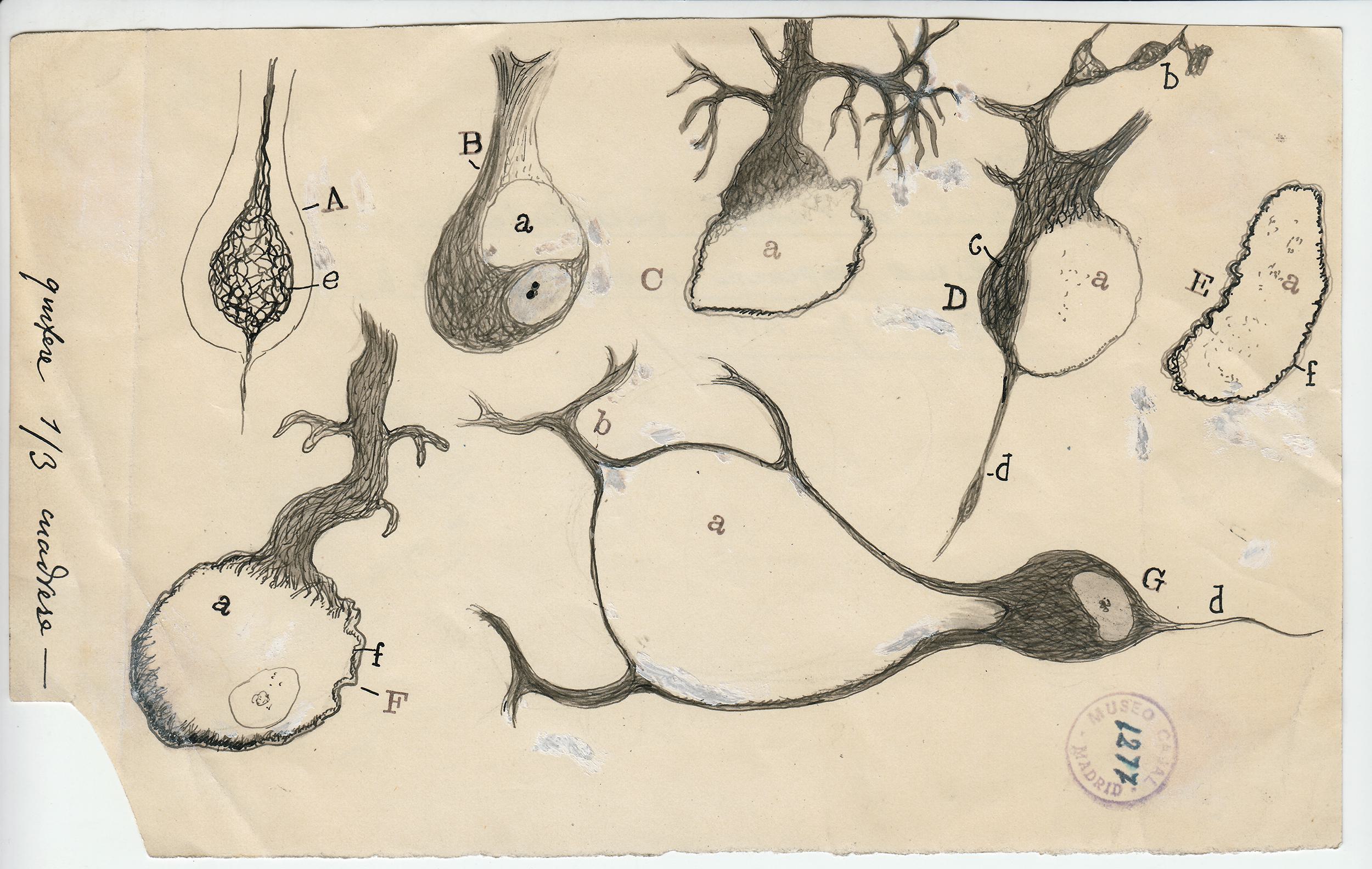

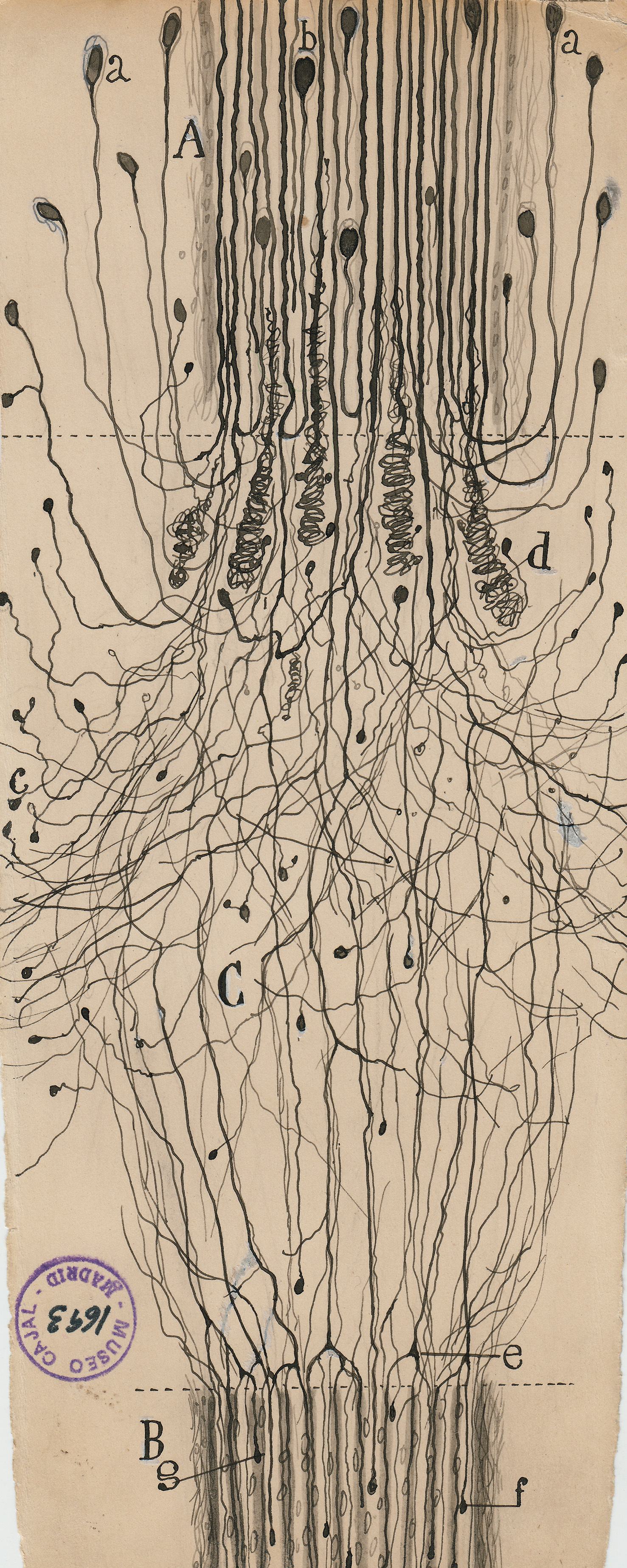

The Spanish neuroscientist felt that to see an object properlyâsay, a Purkinje neuron, with its branches as luxurious as a sea fanâsâhe needed to draw it. But while his freehand pencil-and-ink sketches have mesmerized students of the brain for decades, they were not exact depictions of the cells he had so painstakingly stained and fixed under his microscope. They were interpretations; they were arguments. Cajal drew not just to see but to explain.

Today, more than 80 years after Cajalâs death, neuroscientists have traded their pencils for electron microscopes and MRI machines. These new tools also produce mesmerizing, multi-colored, often computer-animated imagesâpictures that have fueled countless scientific papers and popular accounts of progress in brain science. But they represent a looming trap.

Cajalâs task was to work out the basic microanatomy of the nervous system. He was the first to show that the brain contains billions of discrete cells, rather than an undifferentiated web of neural tissue.

Todayâs neuroscientists are ready to probe deeper kinds of questions. Ultimately, theyâd like to explain how perception, thought, and memory work. They want to know how âthe flower garden of the gray matterâ becomes a habitat for âthe mysterious butterflies of the soul,â as Cajal framed the question in his . Ultimately, though, those are questions about function and integration, not just structure, and the explanations will not be found in images alone.

To visit The Beautiful Brainâa traveling exhibition of 80 of Cajalâs original drawings that landed in the fall of 2018 at the in Cambridge, Massachusettsâis to understand immediately why neuroscience, from its earliest moments, fell under the spell of visualization. Cajalâs drawings are diminutive, often no more than a few inches on a side (the museum supplies visitors with magnifying glasses). But they are alive with texture, depth, and whimsy. The viewer relates to Cajalâs delicate renderings of pyramidal neurons, astrocytes, and blood cells as if they were characters in a graphic novel about cellular survival.

To find another investigator who combined Cajalâs technical ingenuity, deftness with a pen, acuteness of perception, and perseverance, youâd have to go back to Leonardo da Vinci, the first person to systematically document human anatomy. Therein lies the burden of Cajalâs legacy.

The seeming precision of Cajalâs drawings gives them immense narrative power. They were the key weapons he used to overthrow the old reticular theory, which depicted the brain as a single massive network, in favor of his neuron doctrine. This success brought him the 1906 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine. (Ironically, Cajal shared the prize with the Italian pathologist Camillo Golgi, who had invented the staining methods Cajal used to isolate neurons but who remained a lifelong proponent of the reticular theory.)